I miss my dad.

Saying those words, for me, is like saying Chicago can occasionally get “a bit chilly.” My father wasn’t just my dad. He was the best friend I ever had. He “got” me, as did I, him. We had much in common. The music. The Cubs. The same twisted sense of humor. The inability to suffer fools gladly.

He used to say to me, “You know, pal…God forbid one of us gets hit by a train tomorrow…but if it happens, it’s the single greatest feeling in the world knowing there is absolutely nothing unsaid between us. You know I love you because I’ve shown you, and told you, a million times. And you can see my pride in you by simply looking at my face.”

My dad cast a huge shadow, both figuratively and literally. A barrel chested, heavy-set six-foot-one, he had been a musical child prodigy. A master on the piano as a tot, he conducted an orchestra for the first time at age twelve. In the late fifties, he became a jazz pianist whose ardent following reached far beyond his native Chicago, and saw jazz greats like Duke Ellington, Oscar Peterson and George Shearing come listen to HIM play when they were in town. Leaving the club scene behind in the early sixties, he started his own company where he wrote, arranged and produced music for television and radio commercials. Over the next two and a half decades he arguably became the most successful jingle writer-producer ever. To this day, whenever I rattle off some of his most famous jingles to anyone over forty, I’m immediately met with the same two exclamations: “No WAY!! Your DAD wrote that????” Whether writing ubiquitously catchy melodies for Kellogg’s Raisin Bran or Chicken of the Sea (“Ask any mermaid ya’ happen to see…” Yep. That one. You know it.) or producing and arranging the iconic Channel 2 News theme or bringing the STILL played “Here Come The Hawks” song to life, my dad was the epitome of not just musical excellence, but complete integrity and professionalism. He was never late. He was never unprepared. He never had excuses because…wait for it…he never needed any.

My dad was a pro. A musical genius, and a total pro. I revered him. But the truth is, until I was thirteen years old, I didn’t really know him very well.

I was an only child, and the product of my father’s second marriage. (This time to Ruth, my mother.) He’d had three kids from marriage #1 and was nearly forty when I was born. He was also in his first year as business owner in a field that was still somewhat new and just exploding: commercials. His rise to the top was swift, and when I was in grammar school he was averaging three, sometimes four recording sessions a day, all for different companies and products. He’d leave our Highland Park house at 7am, just as I was leaving for school, and be home around 7pm. My mom would make dinner and then he and I both did our respective homework. Mine was mind-numbing history and math; his was writing the next day’s charts for the 8am session downbeat. He not only ran his own company, he built his own state-of-the-art recording studio called Sound Market (at 664 North Michigan Ave) to accommodate the relentless output of creative product. So, there was very little “hang time,” and hence, not much time to play catch with me in the backyard or go fishing. I totally understood, and my sweet and wonderful mother picked up the slack, despite being on many of Dad’s sessions as a singer herself. (I also sang on quite a few “kid oriented” jingles for my dad, starting at age five. It meant I grew up in a recording studio, which was cool…and that I occasionally got out of school to sing, which was even cooler.)

One day when I was about twelve, my dad was driving home on the Edens, flipping the radio dial to decompress from the music he’d created himself that day, when the hit song by Harry Chapin, “Cats In the Cradle,” came on. As it did for many a grown man, the song brought him to tears by holding up a mirror to his relationship with me then, and what it would likely be in the future. He got home and found me in our basement, as usual, blasting music from the killer stereo Dad had bought for himself, but allowed me to use. I could tell from his face that something was up. He was very quiet. Somber. Not himself. Dad seemed always in a pretty good mood. I wondered if I was in some deep shit I wasn’t aware of, and started mentally retracing my twelve year-old steps from the previous days. But he just hugged me, and he hugged me tight. He said, “I love you more than anything in life, son, and I don’t spend enough time with you.” I said, “It’s okay, Dad. I know you’re really busy.” He said, “It’s not okay. And I want it to be different.”

And with that, we began a new phase of our relationship. It wasn’t some cataclysmic change overnight. And it was only a slight moderation of things like throwing a baseball back and forth. But it was more talking. More lingering at the dinner table instead of rushing back into his office to write, or me rushing off to watch “Happy Days.” We started taking more car rides alone together, and any parent can tell you the car is often where great parent-kid talks happen.

Within a year, my father went from being a somewhat mythic figure in my house to my best friend. We shared music with each other. He was the one who first played me “The Stranger” by Billy Joel and “Still Crazy After All These Years” by Paul Simon. I played him “A Night At The Opera” by Queen. We would sit in the basement and listen all the way through. And talk. We watched Cubs games together, and never missed a Muhammed Ali fight on TV. When I left home at eighteen to pursue a career in Los Angeles, I left my mom weeping outside O’Hare airport, and had Dad accompany me for a few days to help me find an apartment. I’d saved enough money to get me through a year, but I was diving into the deep end of life’s pool with no preserver. In LA that week, we found an apartment for me, and Dad saw me sing on my very first record session, for Lionel Richie. We drove around at night and talked for hours and hours. I felt like I knew everything about him. He let me in. Completely. And what I learned only made me love and respect him even more.

I drove him to Burbank airport for his flight back home, and for the first time in my life, I saw my big ol’ bear of a dad completely lose it. He was a wreck, and within seconds, so was I. We hugged each other and sobbed like babies, and in that goodbye became closer than ever before.

My parents moved to LA a couple of years later, and despite my constant state of touring and making albums at the time, we spent a decent amount of time together, defying the story of “Cats In The Cradle.” I got to tell my dad, before I told anyone else, that my wife, Cynthia and I were going to have a child. I actually got to do that three times. As my career progressed, so did my life as a husband, father and businessman. And my father’s counsel, while never volunteered, was indispensable. He was still active musically himself, and we got to do some amazing things together. He wrote arrangements on some of my hit songs (including the gorgeous string quartet chart for “Now and Forever”), and even performed with me in the mid-nineties on The Tonight Show and Arsenio Hall, more than once. We were still thick as thieves, and we talked all the time about how lucky we were to have this special bond.

And then, in 1997, he was gone. Just like that. No warning. No mercy.

My father died as result of a horrible single-vehicle car accident, while driving cross-country from LA to Minocqua, Wisconsin. My parents had bought a summer cabin there when I was ten, and it was the one place Dad could totally decompress. He went there every year, and 1997 would be no exception.

I went into an emotional tailspin that would last….well….it’s never really completely gone away. I was thirty-three, and the father of three boys. But I still needed my dad. Now at nearly fifty, I find I feel just the same. I miss my best friend, and I miss my dad. Always will.

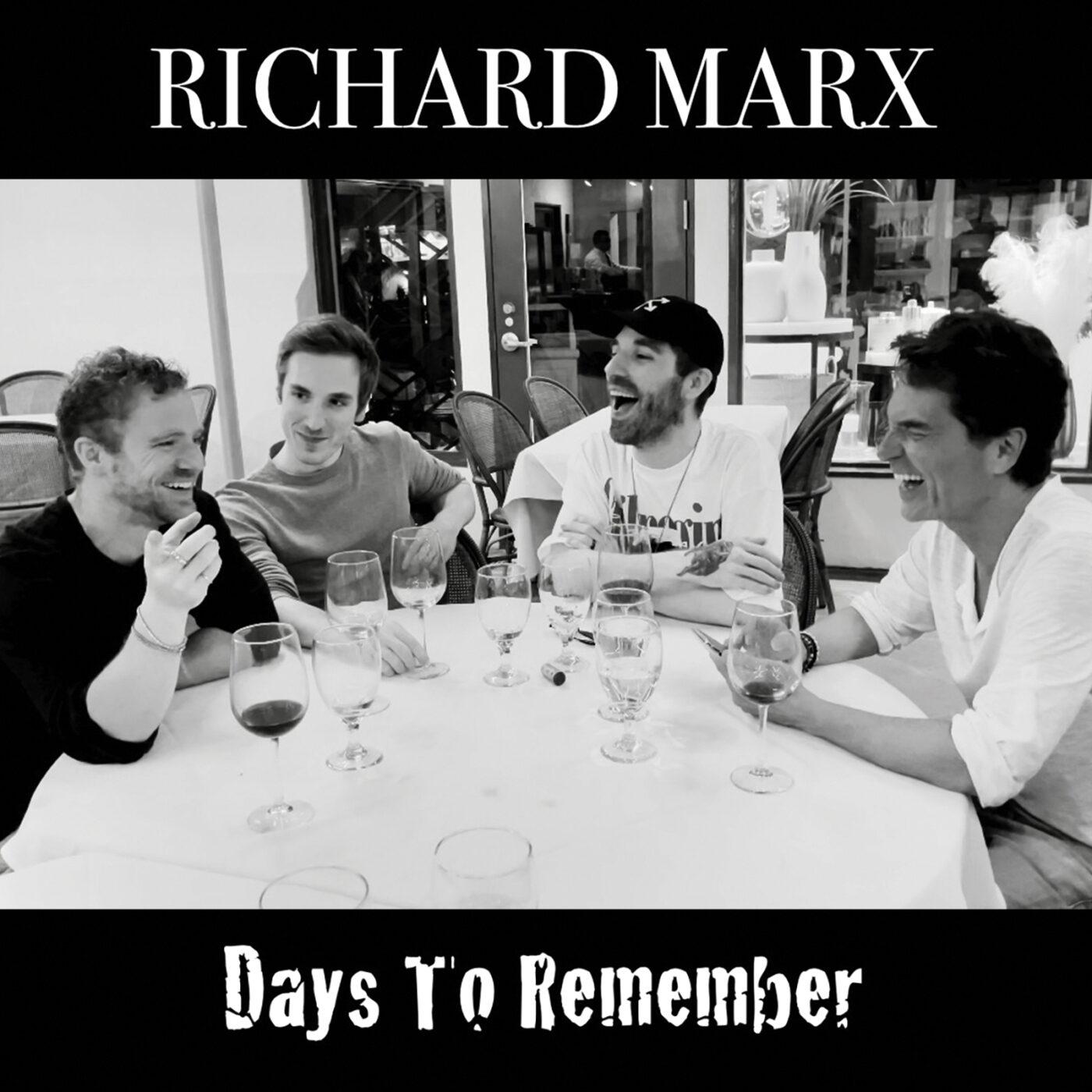

So when Father’s Day comes around, it’s a bittersweet day. I feel I’ve forged a pretty close and special bond with all three of my sons, and I’ve come to view Father’s Day as a dad. But I never see that day show up on my calendar and not feel a lump in my throat. They say “the bigger the personality, the bigger the space they leave behind.” My father was a huge personality, and I’d give anything and everything I have to spend one more Father’s Day with him.

So, hug your dad tight every Father’s Day. And hug him the other 364 days, too.